In the previous post, we examined the general outline of the Five Ways in Thomas Aquinas’ Cosmological Argument for the existence of God. We examined the ways that something can’t come from nothing because the nature of the universe reveals that physical things are dependent upon some kind of outside, transcendent Uncaused Cause, or Unmoved Mover, or Most Perfect Being, or, in short, everyone knows by the term “God.”

Aquinas’ Third Way argues for the existence of God according to principles of contingency and necessity. Let’s begin with a clear outline of the argument:

- Either God exists or God does not exist.

- We observe that everything in the physical world is contingent; it is possible for them not to exist.

- If it is possible for everything in the world not to exist, then, given an infinite amount of time, there would be a point where nothing existed.

- If there is no God, then the universe has no transcendent cause and time must be infinite.

- If at one time nothing existed, then there is no way anything could exist because there would be no-thing to cause some-thing.

All things in the natural world are contingent things, that is they don’t necessarily have to exist. If your computer didn’t exist, the fabric of reality wouldn’t implode. However, if everything is contingent, then why is the universe here at all? If no observable thing hasto exist, then why does anything exist? Therefore, there must be a “Necessary Being,” which is what all men call God.

This third form of the cosmological argument is especially helpful for Christians seeking to defend the reasonableness of faith in God within a culture dominated by Darwinian thought. Evolutionary theory has so saturated the way we think that people no longer think of contingency and necessity in the way that Aquinas or Aristotle did. I often hear Christians reject Darwinian evolution because “It couldn’t just happen,” yet the materialist responds, “Sure it can. Here we are, so it must have just happened.”

“Necessity” in the modern mind has become erroneously associated with evolutionary determinism. Whatever is, must be. Yet once we clarify the logical meaning of contingency and necessity, the cosmological argument become so powerful that even the modern arch enemy of faith, Richard Dawkins, didn’t risk mentioning it in his best-selling book, The God Delusion. If we dare, the common sense of Aquinas can help us clear out the cobwebs of delusion and see again that God’s “eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world in the things that have been made.”[1]

The contingency form of the Cosmological Argument argues for a Necessary Being which is the source of all other contingent beings. It can be difficult to distinguish this Necessary Being of the Third Way from the Uncaused Cause of the Second Form (as briefly outlined in the previous post). Isn’t the cause of existing things the same thing as the source of all being? Not exactly.

As an Aristotelian, Aquinas distinguishes between different kinds of causality. In modern English, we usually only think of efficient causes, or the kinds of causes that create change. Because we are beings who live with in time, it is difficult to think about things outside of time. Our understanding of causality usually always includes a temporal dimension, like the falling of our dominos. First one falls and then hits the other, and the cause of the falling motion is connected to the passage of time. Likewise, when we think of contingency, we usually think about something being dependent upon a cause in the past. However, in the third way of the Cosmological Argument, Aquinas is discussing logical contingency, which is something altogether different from temporal causality. Let’s take an extremely short look at deductive logic and see if we can grasp the difference.

Basic logic works by building deductive arguments. A basic argument includes two propositions which logically entail a third proposition or conclusion. For example:

- All triangles have three sides.

- My slice of pizza has three sides.

- Therefore, my slice of pizza is a triangle.

The conclusion of such a deductive argument is certainly true if the premises, or the first two propositions, are true and the argument follows a valid form. There are two basic kinds of propositions, self-evident and dependent:

- A self-evident proposition is one that is clearly true once both terms in the proposition are understood. For example, “All Triangles have three sides” is self-evident.

- A dependent proposition depends upon an argument to determine its truth value. “My slice of pizza has three sides” is a dependent proposition. It could have been baked and cut as a square.

To begin thinking deductively at all, we have to start with some kind of self-evident premise that is necessarily true. If all propositions were dependent, we wouldn’t have any starting point for our argument! Logic would never work without some self-evident proposition upon which to begin building our deductions.

This is what Aquinas is talking about in the third way of his Cosmological Argument. If we are going to exist at all, we have to have some kind of self-evident or necessarily existingBeing. Now that we are thinking in logical terms instead of temporal terms, let’s look at the specific details of this third cosmological argument. Aquinas uses two key terms in this argument, contingency and necessity.

- Contingency means that it is possible for something to exist or not exist. Consider my argument above; my pizza could be pepperoni or cheese, a triangle shape or a square. There is no logical necessity that the slice of pizza has pepperoni or be a triangle.

- Necessity means that it is impossible for the opposite to exist. Consider the triangle in my argument. Is it possible for my triangle to not have three sides? No, the opposite is not logically possible, therefore this is a self-evident or necessary truth.

Now, by looking at logical propositions, we have a better idea of what Aquinas means by “contingent” and “necessary.” Let’s apply these words now to being instead of propositions. All the things we find in nature are contingent beings because it is logically possible for them NOT to exist. There is no logical reason why the chair I am sitting on couldn’t exist. It certainly does exist, but not by any logical necessity, not in the way that it would be logically impossible for me to be sitting on a four-sided triangle.

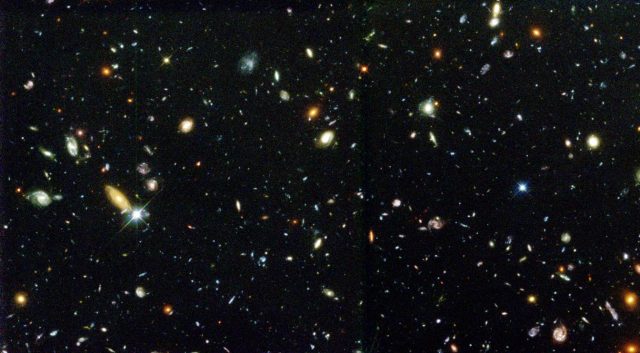

Aquinas also observes that it is in the nature of contingent things to, at some point, no longer exist. Nations rise and fall, humans are born and die, trees grow and decay, even stars are born and die. Given enough time, all natural things come into being and go back out of being. There is no stable, necessary being in natural world, no being that is necessary the way three sides are necessary to a triangle.

At this point in Aquinas’ argument, he powerfully refutes the objection, mentioned in the previous post, that the natural world could itselfbe eternal withoutan Uncaused Cause or Unmoved Mover. Brilliantly, Aquinas points out that given an infinite amount of time – as is assumed by those who argue for an eternal, uncaused cosmos – all possible combinations of being and not-being would occur. This means that at some point, the possible combination of no-being at all would occur. But if there is a moment of no-being at all, then how could something begin to be again after that?! And given an infinite past, we have already had plenty of time for this moment of non-being to happen. Then how are we still here?! Aquinas concludes that an eternal natural world, independent from God, is absurd.

This abstract of an argument can seem slightly bizarre, but let’s reconsider the basic form of an argument again. If all the propositions in the whole world were dependent and none of them were self-evident, then we could have no real arguments and no propositions could ever actually be true. Logically, nothing would necessarily be true; there would be no truth.

Likewise, if all the beings in the whole world were contingent and none of them were self-necessary, then we could have no real source of existence and no things could ever actually exist. Logically, nothing would necessarily exist, there would be no existence.

Clearly, Aquinas argues, this is absurd because things do indeed exist! There must be a self-existing being, a Necessary Being, which, as Aquinas likes to say is “what everyone understands to be God.”

[1]Romans 1:20, ESV.